Apocalypse Arcade

Like many in my country, I’m being encouraged to stay inside right now while CoVid-19 is burning through our cities. I’m spending time with my wife, FaceTiming with relatives and friends, and building a shelf to manage a lot of my older game consoles. I call the last bit Project Retro.

While I was putting the shelf together, I remembered an old gem from the 2014 Writing Challenge I tasked myself with to increase my writing output. Since it makes a good tie-in with Project Retro (more on that in further posts) I thought I’d repost it here. Perhaps it will entertain others who are similarly housebound while we wait for whatever comes next. It’s been edited and polished a little since then, and I feel like it’s good enough to share.

So, welcome to Apocalypse Arcade. I hope you enjoy it.

Pez could see the Market would be slower than usual today. Life had grown languorous in the wasteland’s summer heat. It had not rained for eight days, meaning that all that remained in the bottom of the Market’s water barrels was a rancid and foul sludge. The sour stew that came out of them was oily and dark. Few but the most desperate would drink from such tainted waters.

Growing up in the shadow of Nuñez, the Junk Dealer, meant Pez was comfortable with his thirst. It was the least of the indignities Nuñez had to offer and kept him from the rain barrels. His mother had long since disappeared, and he was unsure of whether or not his mother had even known who his father was. So it was with many of the children of the market whose mothers were whores. It was a common enough origin. Nuñez told him there was nothing to be ashamed of in that. Some of the older residents of the area used the word ‘bastard’ to label him in Pez’s presence, but the small ecology of unwanted human byproduct spawned in the red light district of Market had a purpose. Some wayward children were adopted and taken in to learn a trade such as Pez had been. Many others ended up as slaves or concubines, raised from birth to be molded into the ancient, barbaric roles long known by man. Nuñez had told Pez that in his youth children went to schools to learn without such dark destinies. Pez did not believe him. His own reality was such that he could picture no other life. A place where children were expected to simply sit and listen was a fantasy. Everyone worked in the Market. Everyone pulled their weight. Dullards starved. Abandoned children learned only as much as their profession could provide and their master could teach.

If a child couldn’t hack their master’s trade it was either the gladiatorial pit or starving to death. There were no other alternatives. Not if they wanted to stay anywhere near Market.

Outside of Market a child would not last long on their own.

A wind blew through the dusty concourse of his stall’s corner of the Market. Pez readjusted the bandana covering his lower face to keep out the grit. It was red with white dots and swirls, what Nuñez had called paisley. So long as it covered his mouth Pez didn’t much care for what it looked like or what the style’s name was. It kept the grey grit of the stalls out of his teeth and the ash off of his tongue. It could be called whatever Nuñez liked.

Nuñez’s meager table of dross bore drill bits, toasters, cast-iron skillets, and a few dull knives. The rest was just junk; gewgaws that had no discernible purpose, at least not in Pez’s young eyes. The prized items, at least according to Nuñez, were the old books that Pez couldn’t even read. Nuñez held great stock in books and read frequently. Pez had no need of them. He just wanted to work, to stay out of the pits. He didn’t need to be able to read to do that. He’d learned his numbers at Nuñez’s insistence, at least up to a hundred. As far as he was concerned, he’d never see more than a hundred of anything all at once. Why bother with more?

The grey, ashen haze of mid-afternoon was reaching its brightest. Few stragglers had come to pick through the garbage for sale, but Pez was still keeping his eyes sharp for thieves when a tall traveler appeared in one of the greatcoats from Before.

The traveler said nothing, picking up items and appraising them from behind the cool, reflective gaze of shaded goggles. Gloved hands methodically went over several items. Amongst the pieces handled were the remote for a device that no longer functioned, a radio control with no batteries, and a strange wedge of plastic with another smaller wedge inside, laced with metal. When the stranger’s hands neared several books, Nuñez took interest and came away from his bespoke office. It was a junked van with no wheels, gutted then fitted with a mattress and a desk. A battered solar array along the roof powered its few remaining electrical systems.

“Hola, señor,” Nuñez opened. He tried not to sound too enthusiastic, but with the slow day, Pez could hear the old man ratchet his usual greeting up a notch. Pez looked silently at their new customer, looking over the details of the traveler’s clothes and gear. “Bienvenidos! Welcome to Market! Ingles? Español?

The traveler spoke. The voice was a dry dusty thing and older than his appearance betrayed. “English.”

“You are new to Market, eh? I don’t think I’ve seen you before.”

Pez tried to assess the newcomer’s gear while Nuñez chatted up his mark. Most of it looked fastidiously kept, if eclectic. Were he of a mind to, Pez had no doubt he could sell the man out to some of the less reputable inhabitants Market for a cut of the harvested bounty. He knew that Nuñez would frown upon this. At least before the sale of any goods the man wanted. Pez felt it was always best to keep his options open, though.

“Just passing through,” said the traveler.

“From where?”

“Northeast.”

“Ah, the city? Bad territory for the lone hombre to travel.” Nuñez shifted his voice to a hopeful tone, “You come with a caravan? Bring supplies from another settlement?”

“No.”

Nuñez shrugged, “I suppose not. None of the caravans seem to think much of this place. Always was a small place next to the metro, even Before.”

Before was a time both men knew even if Pez didn’t. Nuñez always sighed when he thought of it. Pez thought it was a waste of breath.

“You look old enough to remember before the war,” Nuñez said with a dry cough as he looked at the man’s collected kit. “You soldado?”

The traveler didn’t respond verbally but nodded ever so slightly. Pez tried to read the traveler’s expression, but could not pierce the flat affect of the stranger’s goggles and ragged filter mask.

“I thought you might say that,” Nuñez said with a grin. “You had the look. Soldado especial? Engineered? They gave you the treatments?”

The stranger did not react to this in any way Pez could see. He figured Nuñez must not see the wisdom of going down that path because he stopped trying to prise out personal information and went back to hawking what was on his table. From what little Pez knew, the soldiers from the war were different somehow. Not to be trifled with.

“You looking for something particular, amigo? I may be able to put you on the right track even if I don’t have anything for you. A little compensation is always appreciated though for a nod to another vendor.”

“Not yet,” said the stranger. “Just passing through and seeing what you might have.” The stranger paused, but the reason was obscured by his goggles. The man gave an audibly dry swallow.

“Well, let me know if there’s something that catches your eye.”

Nuñez was an expert at uncovering the needs of a mark. He could tell what was desired usually by what they carried visibly, how they spoke, and what they wore. He’d been a hawker even before the war, at least that’s what Nuñez boasted when he was drunk on the shine that came out of one of the neighboring stalls. In this instance, Nuñez was backing off.

Pez, however, had a hunch about what the man was interested in and kept an eye on him closely.

The stranger passed the junk table at the front and made his way inward through the stall. Nuñez moved deftly out of his way, keeping his hand near his own pistol. Pez watched the stranger as closely as he could without making himself obvious. His intuition and the stranger’s body language was telling him that the traveler was feigning disinterest. Perhaps Nuñez was starting to lose his sight like most of the old-timers. Pez watched Nuñez retreat back into his van to take in the cool shade.

Pez found himself anxious watching this strange, well-armed newcomer. Through his nervousness, he simply waited for the traveler to pause in front of something so he could get a better look at what had caught the stranger’s eye.

Pez picked out the item almost immediately once the stranger had stopped at an inner table. It was a tangle of junk: a worthless plastic and wood thing, squarish, connected by a lead to a black, plastic box with beveled edges. A rubberized stick popped out from the center of the smaller plastic box on its top side, and a once red but now bleached ochre plastic button was its only other adornment. The larger, wood-panel and plastic box had two long cords coming out of it – one for power and one for something else he had no knowledge of. Pez knew it was electronic, but it didn’t take batteries as far as Pez could tell and it wouldn’t plug into the solar array of Nuñez’s office. So, it had to be junk. Like so much of the rest of the junk that Nuñez typically sold for scrap it held no value Pez could see.

Pez tried again to look into the stranger’s eyes – most buyers gave away tells with their eyes according to Nuñez. The old man would often go on about the eyes being some kind of gateway to the soul. Then again, Nuñez also seemed to believe the rotgut wine he took every Sunday at the Fishers tent was actually blood. Some of the crazy old-timers mumbled over crosses and drank the pretend blood with him, but more often than not, Nuñez wasn’t crazy and he was rarely wrong.

In this case, Pez didn’t need Nuñez’s wisdom or training to see see the stranger’s raw need for the thing. The sheer attachment to the item was playing itself out in the gesture itself. The way the stranger touched it lightly and ran his hand along its surface. In this case, the hands were the giveaway. The stranger touched is as if it was some religious icon or relic.

Pez watched the stranger grab the stick portion of the smaller box with his right hand, then cradle the box in his left placing his left thumb over the disc. He pressed it down to no visible effect, then moved the stick in a circular motion. There was no reaction from the device, but for the briefest moment it looked like the stranger might be smiling beneath his respirator. Pez smiled to match. The stranger was taken by the useless thing. He was sure of it.

Pez reminded himself that for some of the junk, use didn’t always matter. The heart wanted what it wanted. Nuñez had told him that a million times.

“Señor,” said Pez. “You want to buy?”

The traveler considered this and let a silence pass between himself and Pez. Typical buyer behavior. The battle of wills had begun.

Nuñez watched silently from the shade, appraising Pez’s gambit.

Pez knew one of two things would come of this. Either Nuñez would have his hide for speaking out of turn or he’d get a share of the shine next time the adjacent brewmaster had some to spare.

“I don’t have chit or gold. You have currency here?” said the stranger.

“That’s for city trade, señor. We barter here like everyone else.”

“What are you asking?”

Pez heard Nuñez come to the van’s door and lean on its frame to observe his pitch.

The stranger had opened with a question and not an offer. It was typical buyer bullshit, meant to make the seller make the first gesture. The boy turned it around.

“What do you have?”

The traveler turned to leave. Pez and Nuñez shared a sentiment for this kind of thing: they both hated it.

“Señor,” Nuñez intervened, “Are you sure you want to do that? I don’t think you’ll find another one of those elsewhere.”

The traveler turned, “It’s junk. The waste is full of junk.”

Nuñez gave a disapproving look to the stranger.

“How many of those have you come across in the waste?” Pez countered with a little too much eagerness.

The traveler considered this and walked back toward the table. “Then answer me, kid. What do you want for it?”

“MREs,” Pez said. “Bullets, caseless 9mm if you got ‘em. Water is always appreciated.”

“Forget it, kid,” said the traveler. “Isn’t worth that much.” The traveler turned to go.

“I think it is,” Pez pushed. “MREs, okay, maybe that’s too much to ask. Bullets, though, we take other kinds. Most of the zip guns around here are 9 mil, but .22 is just as good, or long rifle .32.” Pez was young, but he knew the ammo market values. You had to or you could find yourself making some spectacularly lopsided trades. “That rifle you got there. That’s a .32, right?”

The traveler popped his rifle off his shoulder and Nuñez took a reflexive step back. Violence was not uncommon in Market, particularly from outsiders who didn’t know the score. Pez stood firm though as the rifle went on the counter and the stranger popped the clip. Three .32 rounds were shelled out onto the table.

“Three caseless.”

Pez looked back quickly at Nuñez for a little guidance. Nuñez looked at him as if to say ‘ask for more,’ so Pez did.

“Five.” Pez knew the stranger wanted the plastic gewgaw badly. The stranger stiffened and looked at him from behind the goggles.

“Four,” he countered.

Pez didn’t look back this time. “Okay, four. Deal.”

It had been much harder to slip away from Nuñez than it was to follow the stranger. Slipping away before it was time was against the rules, upsetting the delicate balance of Nuñez’s life in Market. Even when his smaller expeditions brought something back in, the old man worried. Sometimes that worry turned to anger. Pez had done this before on slim months, the times when Nuñez simply couldn’t pull in enough in trade to keep the stall open. More often than not it brought a beating. Nuñez on occasion called them an ‘object lesson,’ not that Pez knew what that meant.

During slim months when trade was bad, Pez found ways to make profits with deft hands in the market throngs. Nuñez, not without the vice of pride, typically found this kind of thing distasteful. On slim months he did not question the profit Pez brought in on his riskier outings, but this was different. He’d gone on his own initiative, an action that usually resulted in Nuñez taking it out of Pez’s hide. The stranger had something about him worth the risk of tailing him, though. If not, he’d made his peace with the thrashing he would earn.

Pez’s plan was a loose one. He wasn’t here to just steal. The traveler could – likely would – kill him if he was caught. Nuñez had thought the man was soldado especial. While Pez’s own base human greed was probably somewhere in the morass of his motivations, Pez was simply curious. He might never get another chance to see one of the Before soldiers again.

Pez knew he was onto something. He wasn’t sure what yet, so he aimed to find out.

The stranger was tall and that made it easier for Pez to follow him. Pez was small and could weave through the throng of buyers and stalls without notice. Growing up in the shadows of the market had taught Pez the virtue of being dwarfed by adults.

The tall stranger stopped at a few other stalls: a water vendor, then an ammunition seller. The stranger then spent some time at a meat stand, eating skewers of god knew what and slices of the weak peppers that would still grow in the wastes. He hit another junk stall, much like Nuñez’s own. Pez waited for him outside of it for a bit and almost missed the stranger leaving after closing his eyes for a moment. He quickly picked up the stranger’s trail again, locking in on the broad-brimmed hat rising above most of the other market buyers.

Pez pursued the traveler further into Market, toward the higher rent area. Most of the Market was an open-aired sprawl, with vendors forming crude barriers between themselves and other hawkers with corrugated scrap metal sheets, worn linens, or battered planks of wood good for little else than as a line of demarcation. Inside of the rings and crooked avenues of the smaller merchant stalls was Old Market; a large, squat building that seemed impossibly large to Pez. Its exterior had begun to show serious wear and it was obvious that it had not been properly cared for even before the war. Stubborn white paint still clung in spots, but most of it had flaked off in the highly acidic rains and the hard, gritty winds that blew through the plain the market was situated on. Letters Pez couldn’t read were marked in faded green and red and yellow at the building’s front which faced the Long Road that bore most travelers to Market. It was there in Old Market that the stranger headed.

Pez weighed his options. If he was to follow further he’d have to be much more careful. People like Nuñez and the outer Market sellers were suffered at the hands of the people inside the derelict building. People who had stalls inside of the Market proper were pillars of what passed for community. There were more guards here. Pickpockets and thieves were everywhere in the Market, but the class of rogue in Old Market was of a different caliber. Pez would stick out here, even if he wasn’t looking to cutpurses. Vendors of Old Market could afford their own muscle and their own swift and brutal law. He’d been tossed out of Old Market his first week with Nuñez. The guards told him he was bringing down property value, whatever that meant. It was to be his only warning they said, and Pez knew they meant it. Old Market guards had long memories paired with sadistic streaks encouraged by years of watching pit fights.

Pez made up his mind quickly. Nothing ventured, nothing gained as Nuñez liked to say. It wasn’t a crime to look in the Market – he even had four .32 bullets in his pocket that could possibly convince vendors he was a buyer – provided he was stupid enough to wave that kind of wealth around. He had no designs on starting anything, he was smarter than that.

He darted in.

The crowds were looser here and the stranger stood out even more, but so would Pez. He passed several booths and vendors, many of whom were selling shine, companionship, and food. Pez kept his gaze down and made sure not to look like he was loitering when the stranger would stop. Unattended children were frequently abducted and put on the meat markets or sold for gladiatorial sport.

Pez was careful as he followed the stranger through a gambling den, a tattoo stall, a guide station, then to the Slathouse: a place that passed for lodging for passers-through if they had barter to spare.

Pez knew that this would be the end of the line. There’d be no way he could get beyond the Slathouse door without something to pay with. Pez resigned the trip as a wash as the stranger made an offer to the keeper at the threshold of the Slathouse. The offer was taken, and in the stranger went.

Pez went home, disappointed, thinking that he would never see the stranger again.

Pez did, in fact, get a dressing down when he returned. It would not be his first and would be far from his last. He’d certainly had worse at the hands of the pimps who ran the brothels in his earliest years, which was his reason for escaping the brothel in the first place. Nuñez at least had the decency to rarely hit him, and when he did he took care not to strike his face and had never broken a bone. Pez supposed it was the little things. In a few more years he guessed that we would be Nuñez’s size. Then the game’s rules might change.

The next morning dragged by, and Nuñez watched Pez like a hawk, making sure he didn’t get any more funny ideas in his head while he worked. It seemed another boring day was to come and go in the outer rings of the market.

That changed when Pez felt the shadow of the traveler come over him.

His clothes appeared to have been slept in and his outward appearance had not changed a single iota. He only looked briefly, never saying a word. Pez knew better than to engage him. Nuñez’s hands had left their message well. Pez was not looking for another bout of discipline.

The Traveler fixed his goggled eyes on Pez and spoke.

“Televisions. You got Televisions, kid?”

Pez kept his jaw from dropping somehow before he spoke. “Those are rare, mister. And anyway, they’re all just junk. Broken.”

“Then if you got one it’ll be cheap.”

Pez heard Nuñez slip behind him and speak. “Let’s say I did have one.”

“What would you ask for it?”

Pez watched intently as the two men continued.

“It’s not much. But, you ain’t looking to set down roots are you? TV’s big. Liability if you’re just passing through as you said.”

“Last I checked that wasn’t your concern. You got a set or not?”

If Nuñez was taken aback, he didn’t let it show. “Well, step on back. Pez, will you draw the curtain? We’re closed until the man has his say.”

Pez watched the man walk past him and join Nuñez in the back of the stall. In a disused corner, behind a few sheets of plywood, Nuñez had always kept a secure cabinet. The top shelf stuff was in there, and he rarely advertised its existence – only to customers he knew could pay. And even then, he usually sent Pez off while he transacted.

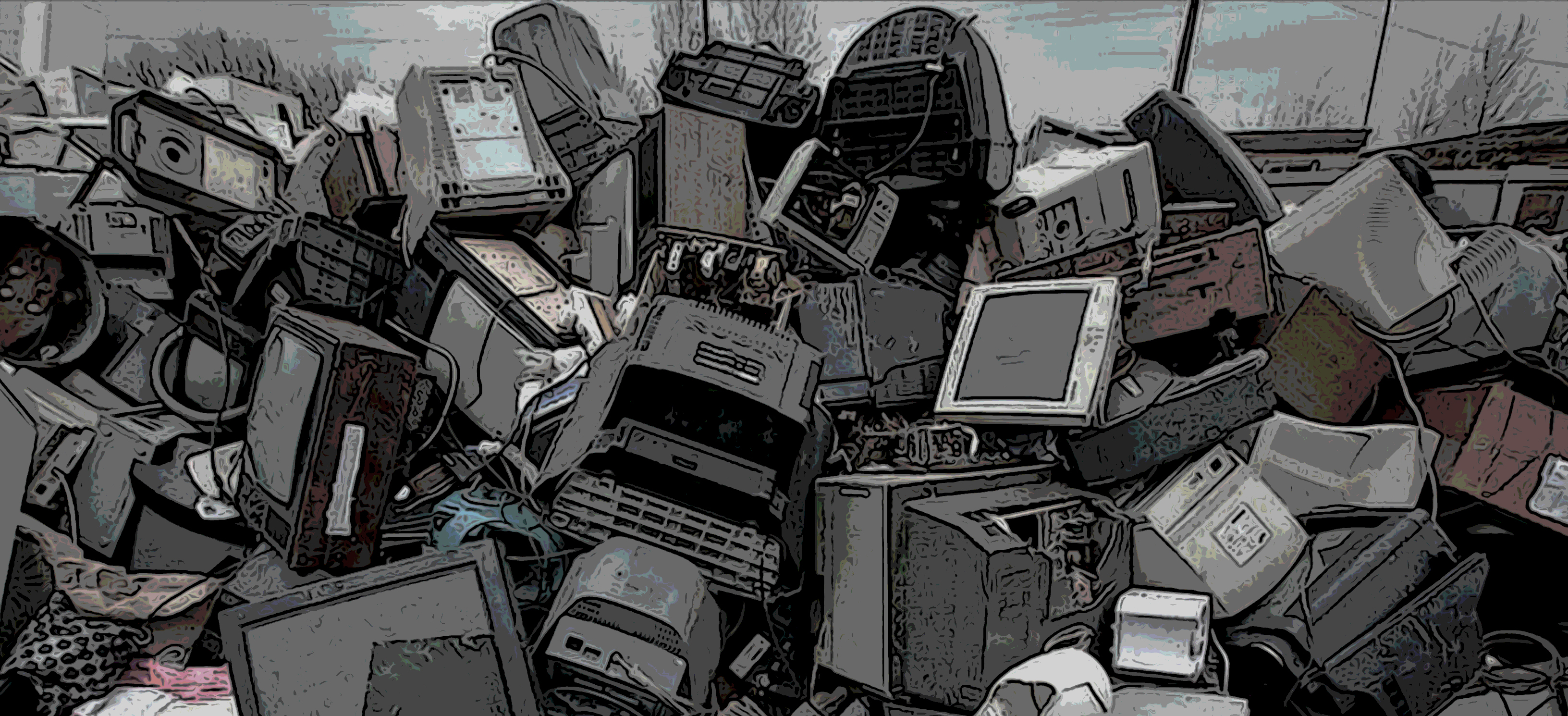

This time though, Pez got a look inside the cabinet. Most of the televisions he saw were old even by Before standards, big boxy things that more often than not were hollowed out and used as a place to light a meager fire or to store things in their shells. This was different. It was on the small side, but its body was flat. It was covered in dust but still held a kind of promise. Of what, Pez had no idea. He knew that they were supposed to show pictures. He’d never seen a functional one and was amazed that one may have been this close all this time.

“Wasn’t plugged in when the EMPs hit or it was out of range,” Nuñez said. “I been holding onto it for twenty years. I guess… I guess I hoped I’d be able to use it again one day. But… I don’t think it’s gonna happen. So… make me an offer, gringo. Before I change my mind.”

The stranger clucked for a bit, looking over the television. “Connections don’t match what you sold me yesterday.”

“Of course they don’t. This was cutting edge when the war started. That old thing you bought yesterday was antique when I was a kid, comprende? Besides, I probably got something here we can use to patch it. Get it going.”

“Let’s say you do. In that case, I’ll give you a full magazine of .38s and three of these.”

The stranger produced from his pack four unopened bottles of purified water, seals intact. It was a ludicrous amount to trade. Clear water with no bugs or grit in it, not muddy or silt-choked. It might not even have to be boiled. The bullets almost seemed like an afterthought by comparison.

“That’s a generous offer. You, ah, don’t mind I check that water?”

“Seals are there, what more do you want?”

Nuñez produced a Geiger counter and ran it over the water. It clicked but not nearly as bad as Pez would have expected it to.

Nuñez didn’t even blink. “I think you got yourself a deal, soldado.”

“I’ll need someone to help me get it over to Old Market.”

Nuñez looked at Pez. “What are you waiting for? Get the cart and help the man.”

Pez carried the surprisingly light television to Old Market where it was revealed that the soldado had purchased a slim stall space, its curtain down. Once past the curtain, it offered only a table, a few battered chairs and a plug installed into the far wall that drew power from a solar array on the roof and a team of enslaved turbine spinners somewhere under the Market. The stranger took the television from Pez without any effort at all and set it on the table.

“You got no idea what it is I’m up to, do you, kid?”

Pez said nothing.

“It’s alright, the guy you’re working for ain’t here. You can speak if you’ve a mind to.”

“I don’t know what any of this is apart from the TV.”

The stranger set his pack down gently onto the table and pulled out the previous day’s purchase. “I had one of these when I was a kid. You read?” he said pointing to the letters on the box’s case.

“No.”

“Says ‘Atari’. You ever heard of one of those?”

“No.”

“Guess you ain’t heard of much from Before then, huh?”

“No.”

“Well, you’re gonna today.”

“Where’d you get the scratch for all of this?” Pez suddenly blurted out. It was a rude question, but he had to ask. This stranger had come from the city to the Northeast and managed to get a stall in the Old Market. Any vendor from Outer Market would have given their eyeteeth for the narrow space.

“Would you believe I used to live here?”

Pez said nothing.

“Well, not here exactly. Maybe two miles to the south. Old development called Wilton Green. Lived with my mom and two sisters. They died during the war. I was fighting in the desert for most of it until the command chain died off.” The stranger looked away from Pez momentarily before adding, “I miss ‘em. I miss the life we used to have.”

“You sound like Nuñez.”

“Lot of old souls do.” The stranger pointed to his duffel. “Hand me those things your owner sold me for the TV.”

“He’s not my owner,” Pez said with unmasked disgust.

“Sorry little man. Didn’t know. I know that people around here take ownership of people who can’t pay debts. I don’t hold with it, but… well, maybe that’ll change someday.”

“Long as there’s a pit master here, there’ll be trade on slaves.”

“I reckon you’re right. But, one thing at a time.”

“You got a name, mister?”

The strange looked at Pez for a moment that seemed too long. Like he’d asked a question that was impossible to answer.

“Mister works for me. That work for you?”

“Sure, I guess.” Pez gave Mister the assorted junk for the television and watched him start making connections. It took a while, but Mister let Pez watch all the same.

“You know, I can’t even remember who showed me one of these the first time. Maybe one of my uncles.”

“Why are you telling me this?”

“You happy back there? Selling stuff for that old guy?”

“I guess. It beat what I had before.”

“I guess it might have. But you never really get a moment do you? A moment when you can just relax?”

“You kidding?”

“No.”

“I work. Everyone works. You don’t work, you go to the pits.”

“Yeah. Sucks doesn’t it?”

They both knew it was a stupid question.

“When I was a kid, before the war, people used to have time. You’d go to school, you maybe did little league, became a scout. But you still might have had time to do whatever. But I remember playing with these.”

Mister finished whatever he was doing and plugged in a power cord from the power box in the wall to the television. Mister hit a button on the ancient thing’s back and its screen cast a blue light so bright that Pez had trouble looking at it.

“Okay, TV works. Now the moment of truth.” Mister flipped a switch on the plastic and wood-paneled box and suddenly the blue was replaced with chunky blobs of random color with a small triangle in the middle of them. The chunks moved and eventually one hit the triangle. It made a noise that made no sense to Pez – but it transfixed him.

“Ah. Wasted a life. This was one of my favorites. Bought it from another vendor on the outside for a .22. Asteroids. I was always good at it.”

Pez saw the man pick up the smaller box with the stick and manipulate it. As he did, the little triangle on the screen moved. When he hit the disc, the triangle fired a pellet that broke up the blobs into smaller chunks.

They said nothing for another half hour while Mister played and Pez watched.

It was dark when Pez returned to Nuñez’s stall. The old man wasn’t angry – he’d had some rotgut to go with his water and greeted Pez warmly.

“The gringo didn’t skin you and eat you. That’s good.”

Pez didn’t say anything else, just came up to his usual seat in the stall. After a few minutes of silence, Nuñez spoke again.

“What’s the matter with you. Cat got your tongue?”

Pez shook his head.

“Kids. I suppose when your balls drop in a year or two, you’ll get even more sullen. But you got time to straighten out. I’ll take care of you.” Nuñez waved an arm in a grandiose arc to indicate his collection of junk. “Someday, all this could be yours.”

Pez had thought about taking over the stall many times before. Old-timers like Nuñez tended to get the Lumps the older they got. Or, they went blind. Or, Bloodlung took them. And when that happened, provided he could keep up stall payments, he could keep the place running.

But he wasn’t sure that mattered any longer.

Not after Atari.

That night he snuck out from the shelter of the van and went to Old Market again. He showed a small disc to the guard who let him inside upon seeing the seal of the Old Market Association on the coin Mister had given him after he’d left. He walked through the place for the first place without fear and appeared at the stall Mister had purchased. He called out and was greeted by Mister who let him in.

“Can I play?” he said excitedly.

“Yeah. You helped me get this set up. Even though I paid you… I think it’s time that you kids ought have some time to see what it was like before.”

It was the first night of many that Pez would return to Mister’s stall. After the crowds died down during the day, Pez would come to the stall to play after hours, sleep for a few more, then hawk junk with Nuñez.

The sun never got any brighter, but Pez’s future did just a little bit.